Why Your Model Isn't Learning: A Debugging Checklist

I wrote down everything I wish I knew before training my first Sequence Model.

Why ML debugging feels different from SWE debugging ?

Debugging model training feels very different from debugging regular code. It demands more attention to detail, more clarity of intent, and the time penalties are higher. especially on limited compute. What makes it frustrating is that many failures don’t crash; they quietly waste days. Most shape errors can be fixed but what cannot be detected upfront is hard to fix. This is probably the biggest reason one cannot just go about vibe coding datasets & models, they require intention and details.

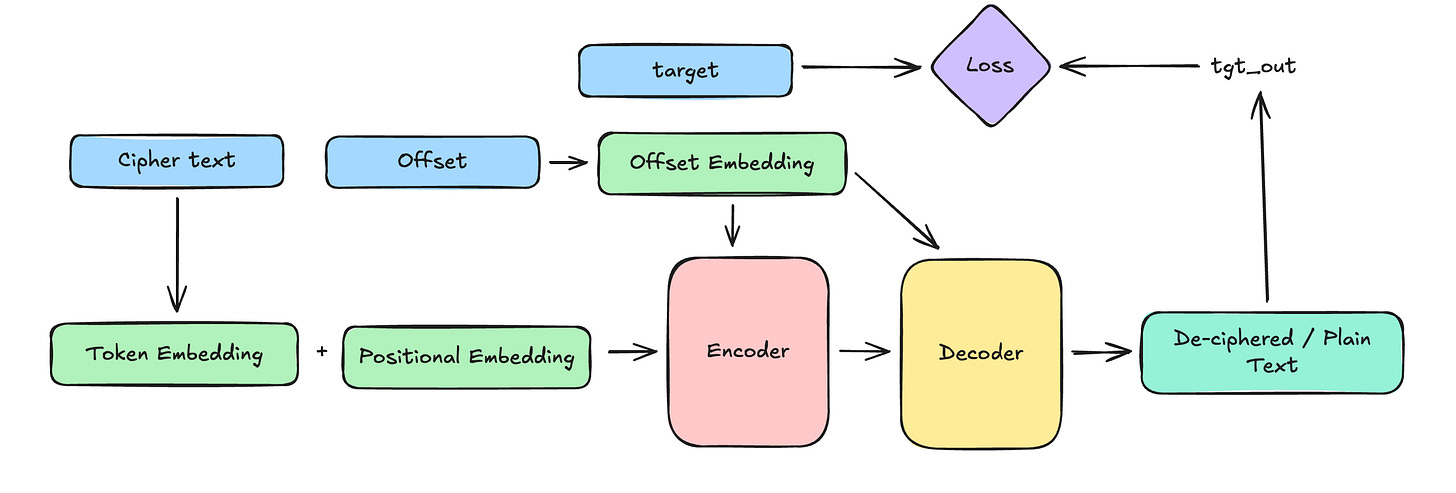

I tried cooking up my own dataset, a toy one, learning the caesars cipher for a fixed offset seemed too easy, so I hacked up a dynamic offset cipher dataset here and thought a simple transformer in an encoder<>decoder seq2seq fashion should be able to learn it. Checkout my repo for the code.

But little did I know all the lessons this simple side-quest would teach me! I will be refering to a lot of examples specific to this instance of training a deciphering model, hence I think its worth sharing what the learning object of the model is briefly through this chart.

The learning objective is fairly straight forward, I wanted to see the seq2seq flow in action to decode some basic ciphers and felt this was the perfect toy task to start playing around with!

In this post is what I wish I had pinned to my wall last month, now a distilled checklist I want to keep returning to while training models and avoid hours of my time I’ve already spent learning the hard lessons. The goal is not completeness, but orientation, knowing what to ask, in what order. This is probably the biggest thing almost nobody talks about and is assumed to always be learnt from experience, but maybe this helps short-circuit your search path through some of the common failure-modes in model training :)

PS: I’m sure there’s gonna be a sequel to this, just a gut feeling.

1. Always start from the “Data + Representation”

“Garbage in, Garbage out. But even giving the right food on the wrong platter can mess things up.”

Think about data both from the dataloaders as well as the model train loop POV’s. I picked up a new habit of starting off the train() loop by having a break and lots of .shape and log.info all over. Also make the ipynb cell debugger your best friend, it will bail you out in the trickiest of situations and in understanding what’s really is going on. Once you can mentally capture the training loop, only then do I free it of the break . I’ve been reminded a bunch to keep all augmentations/transforms inside the dataloader as much as possible, if your train loop is modifying data, something can easily go wrong.

A bunch of traps I avoided by doing this include:

Verifying

offsetin datagen, easy bugs creep in when generating your own dataset. Be super clear about what the dataset was ment for and what you are using it for and how that bridge/transform between what is and what you want can be reached. i.e: this is generally a bunch of data-cleanup tasks.After that, even though my data was correct my embedding layer had only 25 positions ( for offset 1 to 25) but my dataset also included data with 0 offset needing the offset-embedding layer to have 26 mappings, otherwise the model would not be able to represent or get confused when trying to encode some offset ranges!

Even before any modelling, loss curves, metrics, or optimization’s, inspect the data and representations. Don’t just inspect the data at source or in isolation, inspect it in the train() flow! This is the bread, butter, heart and soul of the model, if this is mis-represented or inadequate, we are in for a disaster ranging from Terminator-uprising to monsteras Frankenstein.

The core question:

How could a model learn this mapping, and is that the learning objective I actually want?

Common failure here is conceptual, not technical. The model might learn something, just not what you intended.

What to do :

Log and print raw samples (inputs, targets, special tokens)

Plot distributions (lengths, classes, offsets, etc.)

Manually walk through a few examples and narrate the learning process step by step

Mistakes at this stage are diabolical: everything downstream can look “fine” while learning the wrong thing.

2. Pipeline correctness check

This is about verifying that “the system you built” actually matches “the system you-think-you-built”

This matters most when:

You write custom layers

You compose encoder/decoder stacks manually

You implement your own masking, shifting, or padding logic

Many bugs here do not throw errors, they just silently eat away your sanity until you find them.

Some traps I feel into:

Misaligned

<BOS>,<EOS>betweentgt_in,tgt_outandsrc_in:

I added sequences length cutoff, naive slicing the text excluded<EOS>model gets confused. This could also be solved by solving (1). A simple hack is to sketch out the enc<>dec sequence loop and ask:“If I were the model, and you gave me these exact tokens, would predicting this next token make sense ?”

For example, when both

srcandtgt_inbegin with<BOS>, the model’s first prediction is conditioned on almost no semantic information, yet we still expect it to emit the first real token. That makes the learning signal weak and poorly aligned with the task.Double check causal masks passed to the decoder-self-attention, common trap!

Do you need logits or output tokens when calculating loss? understand loss fn behaviour.

Canonical test:

Overfit a very small subset of data (even a single batch).

If the model cannot drive training loss close to zero on a tiny dataset, something is wrong in the pipeline.

Most of my training bugs weren’t numerical or architectural—they were semantic. The model learned exactly what I asked for, not what I meant. This check can be done in parallel while your looking for the bug, it’ll at least confirm your suspicion instead if it feeling like a witch hunt. This can easily save you lots of GPU time wasted on silly mistakes which can be made and caught on a cheap/local CPU.

This test answers one question only:

“Is the task learnable by this model as implemented?”

3. Is the Optimisation Plumbing Sound?? (Plumbing)

This is about whether gradients can flow and parameters can update. The previous pipeline check if focused more on the forward pass, while this is focused more on the essence of backprop doing its job.

A simple, low-tech approach is often enough but, hey! nobody is stopping you from plugging in that tensor-board if you know how to :)

What to check:

Loss decreases at all ?

Gradients exist where you expect them (check earlier layers)

After loss.backward() and before optimizer.step(), check whether embedding parameters or the first layer weights have non-zero gradients.

Non-zero gradients mean:

There exists a differentiable path from loss to that parameter

The optimizer can update it

This does not mean the parameter is important, only that it is connected.

Some generic solutions here: normalization’s, gradient clipping, residual connections etc. But you should know best about the model you’re building, so the choice is yours!

The mental model:

Can it learn at all? (plumbing)

Are gradients non-zero?

Are tensors connected correctly?

Is loss decreasing?

4. What is the model actually learning? (Conditioning)

Even if training “works,” the model may be learning a shortcut.

The question here:

Does the output casually depend on the inputs I care about?

What we mean by the above is that we want the output y to be dependent of input x, in probability talk, P(y | x), but in sequence models, its very possible that the model finds shortcuts to minimise loss by learning from previous prev_y, i.e: ongoing sequence gen. This means the output is not longer conditioned on the input instead, its being conditioned on the ongoing output generation, P(y | y_prev). This is common in language modelling tasks, it can get away by recognising and picking up patterns from the english language instead of actually learning what your are trying to teach it in order to reduce the loss!

This is tested via interventions, not metrics.

Examples

Shuffle encoder inputs while keeping targets fixed

Provide wrong conditioning variables (e.g., wrong offset)

Drop conditioning entirely

Expected behaviour:

If the model depends on a signal, breaking it should hurt performance

If performance barely changes, that signal is being ignored and what you want is not being to learnt or what you want itself might need another think.

Example: Imagine you found out the encoder output is being completely ignored and you could’ve just trained the decoder for half the params/time/cost ! Big save ain’t it?

This distinguishes genuine conditioning from accidental correlation.

5. Is capacity appropriate? (Model Size)

Only after correctness and conditioning are established does model size matter. Note that the below suggestions assume the previously discussed pitfalls have be avoided/mitigated.

Key questions:

Q: Can it fit a simple version of the task quickly?

If training is not driving loss down on a sizeable dataset, its a capacity bottleneck or your “plumbing” is broken, go back to the previous sections!

Q: Does it under-fit even trivial variants?

It should NOT, we are looking for quick overfitting on trivial stuff here! If the model cannot overfit even a small sample set then its a capacity constraint, the model just doesn’t have enough knobs for tuning to approximate your target function(learning objective).

Q: Does performance saturate early despite clean gradients?

This is a tricky one but here are the broad cases:

Case A: Capacity Limitation

Training loss plateaus

Validation loss tracks training loss

More epochs do nothing

Model fits simple tasks but not full task

Solution: Bigger Model

Case B: Insufficient Training Data

Training loss continues to decrease slowly

Validation loss plateaus or worsens

Train–val gap grows

Solution: Get more data, add regularisation.

Case C: Optimization Limited

Loss decreases, but painfully slowly

Gradients are tiny but nonzero

Model eventually improves

Solution: up the

lr, pick a different/better optimizer, add normalisation.

But the most important thing is that, this is the point in time where scaling experiments belong, not earlier. Its easy to fall the trap of “training bigger models” which can sometimes work but might not always be necessary and worse in other cases, even the bigger models don’t learn and just send you in excruciatingly slow loops of debugging model train()’s.

6. Getting un-stuck: Hypothesis-Driven Debugging

When stuck, stop poking randomly. This is where I had to step back from my usual SWE debugging habits, we are not looking for a line number from the stack-trace. The bug is likely not in the code and but in my understanding, code can only be the vessel used to discover the conceptual bug in my head, but no amount of just code-fixing / swapping-layers / picking-better-tuning-params will bring me results.

The best thing to do is - Write a falsifiable hypothesis

If the model is doing X,

then perturbation Y should cause behaviour Z.

Then write the smallest piece of code and use the smallest piece of data & compute to test it. Once again be aware of all the previous traps, they can reappear in these smaller side-quests!

Example

Hypothesis: the decoder is ignoring encoder outputs

Test: shuffle encoder inputs while keeping targets fixed forcing a intentional mismatch between inputs and target. The model should obviously get confused and not learn well.

Observation:

Loss increases → encoder is used

Loss unchanged → decoder-only shortcut

Always start with data and objective-level hypotheses before diving deeper into the model. This will both build your confidence in the model and also the model’s confidence on its predictions. This is were we borderline between engineering and doing science !

7. When the model just “doesn’t learn”

You will ideally need to revisit one of the steps above, but heres a quick pointer on what you can try first. There are two distinct failure modes:

Loss does not improve

Likely pipeline or optimization issue

Re-check data, masking, loss alignment, gradients

Loss improves, but behaviour is wrong

Likely shortcut learning or missing conditioning

Run ablations and adversarial evaluations

Confusing these two leads to wasted time and misguided fixes.

Conclusion

Debugging models is not harder than debugging code it’s different (hence hard? lol, only for now I guess!)

The main difference is the mindset shift, I no longer need to think about the rules of the compiler, the questions have changed, what is being debugged here is more than just code. You are debugging:

distributions, not values

causal dependence, not control flow

optimization dynamics, not logic branches

Once I internalized this, the process became slower per step, but dramatically faster per insight. This reminded me of a random Naval quote which i’ll end with, Ciao!

“The only true test of intelligence is whether you get what you want out of life” (or the model you trying to train). - Naval